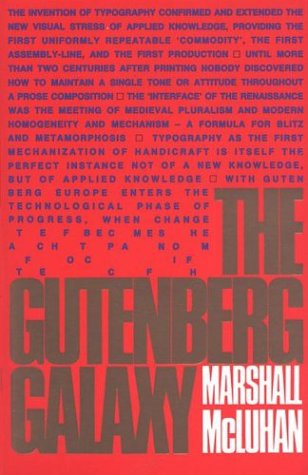

The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man

by Marshall McLuhan

What is The Gutenberg Galaxy? It is McLuhan’s term to describe the post-printing press world, and it is home to a whole lot of knowledge, thoughts, and ideas. In short, you might say that the galaxy consists of anything that’s ever been printed. The Wikipedia page for this book has an estimate for just how big the Gutenberg galaxy might be: in 2004/2005, the British Library had more than 97 million items, while the Library of Congress had more than 130 million.

Reading The Gutenberg Galaxy was kind of like what I imagine running a marathon feels like – grueling and intensely difficult, but ultimately rewarding when you get to the finish line and reflect on what you’ve just done.

This book took me an extremely long time to get through. The text is dense, full of paradoxes and passages you might have to read two or three times to obtain even 25% comprehension (or maybe that’s just me), and the writing style seems almost arcane. It must have taken me at least three months to read this book. Granted, I’ve been extremely busy with teaching and tutoring, but that’s still a long time (even for someone like myself with self-diagnosed reading ADD).

I was relieved to read that Douglas Coupland is with me on this one. In his biography of McLuhan, he describes The Gutenberg Galaxy as “possibly one of the most difficult to read yet ultimately rewarding books of the twentieth century. It explains so much, all the while taking the reader on side journeys into charming cul-de-sacs and odd dead ends.”

The side journeys, cul-de-sacs and odd dead ends are mostly due to McLuhan’s odd mosaic style and bizarre ability to jump from one obscure text to the next, surfing his way through many passages picked out from all areas of the Gutenberg galaxy.

The mosaic is composed of 107 short chapters, most of which consist of dissecting a passage of text from a book, poem, article, or some other piece of writing. For instance, in one chapter entitled The modern physicist is at home with oriental field theory, McLuhan pulls a passage fromWerner Heisenberg (the physicist who is credited with developing the uncertainty principle of quantum theory), who had quoted a tale of the Chinese sage Chuang-Tzu in The Physicist’s Conception of Nature. In this tale, a peasant farmer is presented with the opportunity to enter the Industrial Age and use mechanical machines to do his farming. But the farmer replies:

“I have heard my teacher say that whoever uses machine does all his work like a machine. He who does his work like a machine grows a heart like a machine, and he who carries the heart of a machine in his breast loses his simplicity. He who has lost his simplicity becomes unsure in the strivings of his soul. Uncertainty in the strivings of the soul is something which does not agree with honest sense. It is not that I do not know of such things; I am ashamed to use them.â€

After each passage in the book, McLuhan offers his thoughts on the piece: ‘“uncertainty in the strivings of the soul†is perhaps one of the aptest descriptions of man’s condition in our modern crisis; technology, the machine, has spread through the world to a degree that our Chinese sage could not have even suspected.’

These are McLuhan’s words from 1962, but oddly, they seem more fitting in 2011. I can only imagine that people in the year 2061 will think the same. 49 years after McLuhan wrote of the machine’s spread, our world’s technology has devoured us to a point that even McLuhan could not have possibly imagined. Every 12 year old has a 1 GHz processor in his or her smartphone, Tweet and Google are verbs, and we’ve become so addicted to our gadgets, we’ve had to create laws so we don’t use them while we drive. What would Marshall think?

This is the first book of McLuhan’s that I’ve read (although I just picked up Understanding Media at Pulp Fiction books a little while ago), and I’m in the process of reading Coupland’s biography of McLuhan at the moment. Marshall (as Coupland refers to him) was simply a fascinating individual, and it’s a shame that more Canadians aren’t aware of his contributions to the 20th century. If it were up to me, I’d make some passages of his writing required reading for high schoolers in Canada. I think that through analyzing McLuhan’s work and seeing our history broken up into 4 eras (Oral tribe culture, Manuscript culture, Gutenberg galaxy, Electronic age), many students would be able to realize just how different the world has become in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. I get the impression that kids in our school don’t really appreciate how different it was to grow up without the internet, for example. I’ve told my students before that they’re about the same age as Google, and they’re shocked! They can’t believe that I was in already in grade 8 the first time I used Google to search for something. Reading McLuhan would give many students some context – a macroscopic look at our world’s history, told through the lens of media.

The copy of the book I had came from the Vancouver Public Library (VPL), and having this old hardcover copy to read was especially fitting for a book such as this. As I contemplate buying an eReader, analyzing the pros and cons of print and digital books, it was surprisingly refreshing to read a book that is nearly 50 years old, turning its yellowing pages and even seeing past readers’ pencil marks, notes, and musings. I actually really enjoy it when I get something from the VPL and there are thoughts jotted down in the margin (at least if it’s done right). Whoever was marking this book appears to have been  a professor who was using the book for his or her class. It was neat to see which passages stood out to that reader, although I have to wonder if these markings influence my own reading of the book, drawing attention to things I might have interpreted differently in a brand new copy. Will this form of reading be lost in the digital age? What will eReading eventually look like? Will we be interacting with other readers of the book in interactive editions? Will books just become shorter? Will anyone care to read something like The Gutenberg Galaxy in an era of eBooks?

For my last question, my guess is no, and that’s a shame. At the very least, the Wikipedia entry for The Gutenberg Galaxy is a good start, and at least lays out the structure of McLuhan’s major ideas. I think there are passages of sheer brilliance contained in McLuhan’s book, and I hope to be able to utilize them in a classroom some day.

Note: This started out as a review of the book, but gradually became something else. If you’ve actually read this far, hopefully reading this post didn’t feel like running a marathon. I feel like I’ll be coming back to McLuhan’s writings at least a few more times in my life, and I hope to soon dig deeper into some quotes and passages from this book. I took a lot of notes for this one.