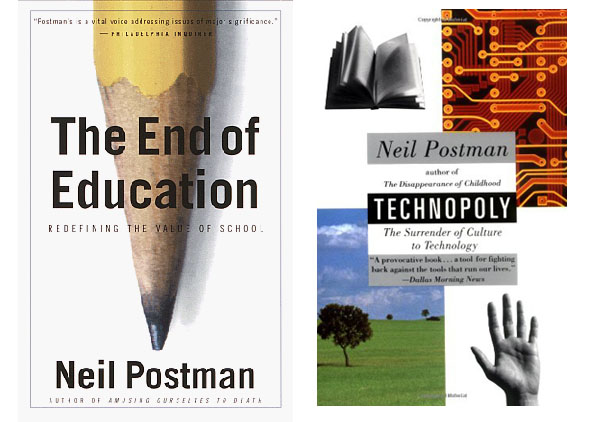

What do I actually do on the Internet? I have been thinking about this and more, as I contemplate what the Internet is doing to our brains, culture and society. By reading The Shallows (Nicholas Carr), Macrowikinomics (Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams), and a host of others, such as some of BrainPickings‘ list of seven must-read books about the future of the Internet, I’m realizing that this can be quite a polarized debate. Clay Shirky’s latest, Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age, gives us a rational, optimistic, and grand view of what the internet is doing to us, how it’s happening, and what it means.

In this quick and thought-provoking read, internet guru Clay Shirky writes about the effect that the Internet is having on our society. He defines and explains the book’s title in the opening chapter: “The cognitive surplus, newly forged from previously disconnected islands of time and talent, is just raw material. To get any value out of it, we have to make it mean or do things.  We, collectively, aren’t just the source of the surplus; we are also the people designing its use, by our participation and by the things we expect of one another as we wrestle together with our new connectedness.â€

We, collectively, aren’t just the source of the surplus; we are also the people designing its use, by our participation and by the things we expect of one another as we wrestle together with our new connectedness.â€

The book opens by comparing our transition into the digital age to that of the Industrial Age in 18th century London. (If this sounds very familiar, you may have read something similar in Tapscott and Williams’ Macrowikinmoics, or seen Tapscott speak about it on CBC’s Mansbridge One-On-One.)

Shirky tells the story of London’s excessive gin drinking, brought on by society’s inability to adapt to the massive change that was going on around them. The gin drinking consumed all aspects of the Londoners’ lives, taking up most of their free time. In our shift to the digital age, Shirky says that our escape, our gin so to speak, has been the sitcom. The Londoners of the 1720’s drank gin; the North Americans of the 20th century watched Gillian’s Island. We watched Cheers, Seinfeld, and The Simpsons. When we came home from work, we turned on the TV, even if we had nothing to watch.

Internet > TV

In 2011, that trend is shifting. When we come home from work, we open the laptop. We don’t even really need to check anything in particular; we just turn it on out of habit. Our Gilligan’s Island no longer exists. The Internet creates diversity by offering personalized content, and for the first time in human history, offers to the masses the ability to produce and contribute to the media, rather than just consume and observe. Increasingly, more people are spending their free time on the Internet, contributing their cognitive surplus to the world wide web. The effect this is having on society is profound, and Shirky looks at how our tools connect us more than ever before, why we contribute and share with strangers, and what it ultimately means for mankind.

The Paradox of Revolution

In one of the book’s strongest sections,  Shirky compares this digital revolution of the 20th and 21st centuries to the 15th century’s transition into a world of print. He tells the story of Gutenberg and his printings of Bibles and indulgences (granted by the Catholic Church after the sinner has confessed and been forgiven), which at first glance seemed like they would further strengthen the “economic and political position of the Church”. Instead, just the opposite happened.

According to Shirky, “This is the paradox of revolution. The bigger the opportunity offered by new tools, the less completely anyone can extrapolate the future from the previous shape of society. So it is today. The communications tools we now have, which a mere decade ago seemed to offer an improvement to the twentieth-century media landscape, are now seen to be rapidly eroding it instead.”

The changes happening in our world as we adjust to the digital world of computers and the connectivity of the Internet are comparable to the changes that occurred in the 15th and 16th centuries as a result of the printing press and the subsequent flood of information.

The Spectrum of Internet Use: Personal, Communal, Public, Civic

In chapter 6, Shirky demonstrates how “the organization of sharing has many forms” and points out that “we can identify four essential points on the spectrum”. The four essential points are:

- Personal sharing: “done among otherwise uncoordinated individuals” (eg. ICanHasCheezburger, most general uses of Facebook etc)

- Communal sharing: “takes place inside a group of collaborators” (eg. Meetup.com)

- Public sharing: “when a group of collaborators actively wants to create a public resource” (eg. open-source software such as Linux and Apache, WordPress, Wikipedia, etc)

- Civic sharing: “when a group is actively trying to transform society” (eg. Pink Chaddi, organized protests in Tunisia, Egypt etc.)

Shirky argues that personal sharing is not as beneficial to society:

“We should care more about public and civic value than about personal or communal value because society benefits more from them, but also because public and civic value are harder to create.â€

He goes on to he draw from a previous reference to the Invisible College, a group of intellectuals in 17th century England who shared ideas and laid the foundations for modern science. Shirky cleverly lays out the choices the internet offers us:

Music shared like thoughts, rather than like objects. Bits of information, rather than atoms of matter.

This distinction makes a world of difference.

Final Thoughts