“Why history and geography? Why not cybernetics and ecology? Why economics and algebra? Why not anthropology and psycho-linguistics? It is difficult to escape the feeling that a conventional curriculum is quite arbitrary in selecting the “subjects” to be studied. The implications of this are worth pondering.”

“What’s worth knowing? How do you decide? What are some ways to go about getting to know what’s worth knowing?”

– a couple of the many questions asked in the chapter “What’s Worth Knowing” from Teaching as a Subversive Activity

Neil Postman

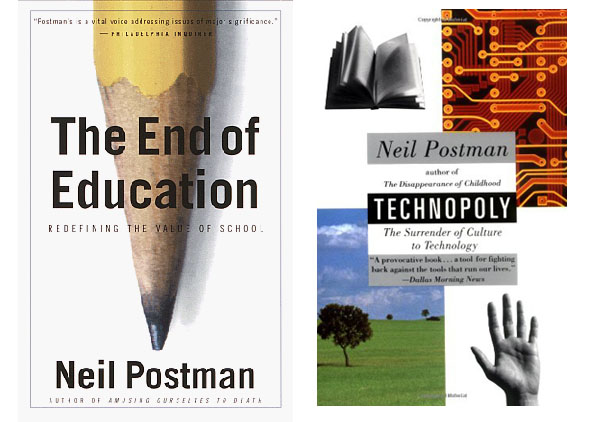

As I’ve been “learning how to teach” for the past six months, I’ve been reading a number of Neil Postman books in my spare time. Postman has been called a media theorist, cultural critic, and a teacher, to name a few. He is the author of 18 books and over 200 articles or essays, many of which were concentrated on the role of education in society, such as 1995’s The End of Education, 1993’s Technopoly, and 1967’s Teaching as a Subversive Activity (co-authored with Charles Weingartner). I read The End of Education and Technopoly back-to-back (you can read a bit about them here) a short while ago, and have now started to read this older book, written over 40 years ago.

As I’m reading Teaching as a Subversive Activity, with all of its references to the Cold War, these new machines known as computers, and the new education (aka education reform), I’m taken aback by how relevant the book still feels. Many of the questions Postman ponders, the critiques he slams down, and the suggestions he makes are still entirely applicable to the world of education in 2011.

Why is that? I think that many of the suggestions made in Postman’s 1967 work were so radical for their time, they are just now seeing the light of day in North American classrooms. It takes time for change to occur.

The Historical Perspective

Neil Postman has a countless number of ideas about the role and process of education. One of the ideas that has stuck with me is that he believes every subject should be taught from an historical perspective. That is, the content of the course should be given context by examining it through an historical lens. One should learn and teach some history about the subject, rather than just teaching the basics of the subject. For example, in Science class, if your goal is to teach high school students about the stars and planets, you have to guide them to discover what people used to think, and how they discovered what they know. You might want to teach students that for thousands of years, humans thought the Earth was the center of everything, with the Sun, moon, and “wandering stars” (the planets) moving around the Earth. It wasn’t until the 16th century that this idea was formally turned on its head by Nicolaus Copernicus (among others) and it would be much later until the general public accepted this idea. By approaching a topic such as the solar system with an historical approach, students would see that science is a ongoing process and realize that what we know now is not the end of the line. There are still many discoveries to be made, and understanding the past can guide us towards understanding the present and perhaps more importantly, the future.

Exploring the past helps us to understand how we got here, which in turn assists us in comprehending where we’re at in the big picture of Earth’s history, and can ultimately help to direct us to where we’re going. I think that this historical approach can be used effectively in any subject, from Math and Science to Art and PE.

The McLuhan Connection

One thing I recently discovered is that Postman was good friends with perhaps the most well-known media theorist, and cultural critic of all time, the man Wired magazine named its ‘patron saint’, Marshall McLuhan. McLuhan was a Canadian educator, philosopher, and media critic. He was perhaps most famous for coining the phrase “the medium is the message”, in attempting to explain the influence that our media have on us. I’m just recently discovering McLuhan’s writings, and am eager to get reading them. I recently had some good finds at used book store, picking up McLuhan’s most well-known book, 1964’s Understanding Media (for $4.50!) and Donald Theall’s analysis/biography, The Virtual Marshall McLuhan. And the new Vancouver Public Library site has lead me to The Gutenberg Galaxy and Douglas Coupland’s biography of McLuhan. Hopefully I can find some time to read them during my practicum.